Mauricio C. Serafim | 20.11.2025

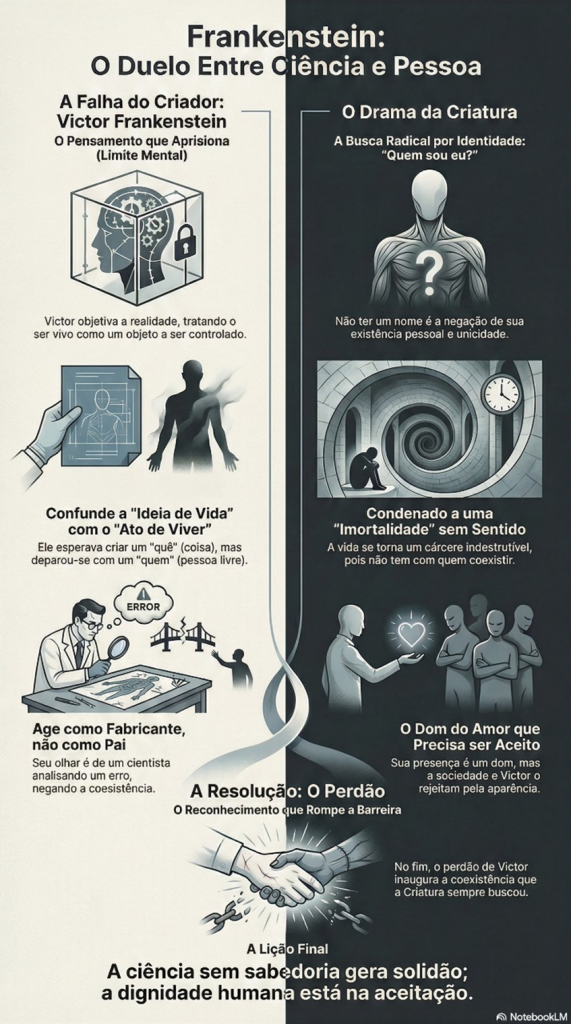

The film illustrates the conflict between technical production and the personal dimension. The Creature’s misfortune does not lie in its monstrous constitution, but in the systematic denial of fully manifesting its transcendentals (free coexistence, personal knowing, personal loving), a direct result of its creator’s inability to overcome the limit of objectifying thought.

To understand Victor’s failure, we must turn to the theory of knowledge of Leonardo Polo. The mental limit consists in the fact that our thought objectifies reality: we paralyze the flow of being to possess it as an object (ob-jectum).

Victor Frankenstein is the archetype of rationalism that cannot abandon the limit. He acts as an expert technician: he manipulates nature—flesh, nerves, electricity—and dominates physical causality. However, he confuses the idea of life with the act of living. While thought objectifies and controls, the human person is an unrestricted and free act of being. Upon seeing the Creature awaken, Victor suffers a shock: he is confronted with a who (an uncontrollable freedom) where he expected a what. His horror is metaphysical: he closes himself within his mental limit, refusing to acknowledge that the Creature’s person infinitely exceeds his projected idea.

This confinement in the mental limit prevents Victor from exercising coexistence. In Polo’s approach, the person is constitutively “being-with” (cum alio). The Creature, although ab alio (coming from another), has its cum alio (being with the other) denied. The monster becomes an ontological orphan. It seeks the father’s gaze to be confirmed in its being, but finds only the analytical gaze of a scientist who sees an error. And when it realizes it will never have this gaze, it begs Victor to make it a companion like itself, its replica—in Polo’s language—someone who could know and coexist with it. When this wish is denied, it revolts against its creator, stating: “You were my creator, but now I will be your master!”

The Creature’s anguish manifests personal knowing (intellectus ut actus). Unlike Victor’s knowledge, which seeks to dominate nature, the Creature’s intellect seeks identity. The question that moves it is not technical (how was I made?), but radically personal (who am I?).

This drama is aggravated by the fact that the Creature does not have a name. The proper name is the recognition of the uniqueness of the who. Symbolically, to have no name is to have no existence. He is an unnamed being, a being without designation, which makes his search for identity an abyss: how to reach the truth about himself, if he is denied the very vocative by which one is called into existence? The absence of the name is the maximum negation of his personal intimacy.

However, there is one aspect that makes the anthropological tragedy absolute: the inability to die. Victor, in his technical zeal, overcame the biological barrier of death, granting the Creature indestructible resilience.

From the perspective of Polo’s approach, this is an aberration. Human life is temporality oriented towards an end (destiny). By removing the possibility of physical death, Victor did not confer glorious immortality, but imprisoned the person in a perpetual duration without meaning. Death, for the wounded man, can be a transit or a relief. For the Creature, life became an indestructible prison.

It is obligated to be indefinitely without anyone wanting to be with it. It is the radicalization of solitude in time. If the person is coexistence, being immortal in solitude is the most painful contradiction possible: it is an act of being that persists, but which cannot be realized, as it has no one with whom to share its forced eternity.

Finally, the transcendental of Loving is revealed in the dual structure of giving and accepting. We see the Creature’s initial innocence, which offers its presence as a gift. However, for love to be realized, the gift must be accepted.

Society, mimicking Victor’s error, clings to appearance and refuses this donation. Rejected love sickens. There is, however, the episode of the encounter with the wise old man. In this moment, the mental limit is overcome: the blind man, not distracted by the image, perceives the personal presence and accepts the companionship. There, coexistence is experienced: monstrosity disappears when there is welcoming.

However, the true resolution of the anthropological drama occurs only in the final minutes. The Creature’s tragedy—a being without a name, condemned to an interminable duration and destitute of filiation—seemed to head towards an outcome of absolute solitude. Nevertheless, the work reserves a metaphysical twist for us in its final moments. Victor’s mental limit, which throughout the plot objectified the Creature, finally breaks. By sustaining the gaze of his creation and asking for forgiveness, the scientist performs the act of personal recognition that was so lacking.

From this perspective, Frankenstein (2025) is a warning about the dangers of a science that does not abandon the mental limit. Victor created an indestructible nature, but was unable to welcome the person, because he tried to reduce the mystery of freedom to the measure of his technical understanding.

The lesson is that human dignity is not sustained by biological perfection, but by the acceptance of the act of being. The Creature possesses personal knowing and loving, but it is obscured because its creator, a prisoner of himself, refused to exercise fatherhood, which is nothing more than the highest form of coexistence. However, the final act of contrition and recognition alters the substance of the entire narrative. The tragedy of the monster without a name and without death finds its rest in that instant of forgiveness. By looking into the eyes and being looked back at, coexistence is inaugurated. Victor ceases to be the manufacturer to finally become a father.

The film teaches us that science without wisdom produces solitude, but also that the human person is irreducible: it cries out for love until the end. And when that love is granted—even if in a belated request for forgiveness—dignity is restored and the abyss between the I and the thou is, finally, overcome.